I attend a Mennonite Church.

This might seem an unusual choice for me, because I certainly orbit on the outer fringes of mainstream Christianity. I first stumbled across Mennonites when I lived in Upstate New York. I drove past a little Mennonite USA fellowship for two years before I got the courage to try it out. All I knew at the time was that Mennonites are cousins of the Amish, and that they are staunch pacifists. I wasn’t sure what to expect the first time I entered the church; would I be out of place not wearing a head covering or plain clothes? Would I be way too progressive for them?

As it turned out, I fit into that church quite nicely, and they helped continue me on my journey of exploration into pacifism, non-violence, and how we as humans should approach pain and suffering in life.

Fast forward a few years – I am now back in Indianapolis. Once again I found myself hovering around the edges of Christianity, unsure if I wanted to be in or out. And once again, I stumbled across a Mennonite church, and again, it is the right fit for me. It’s a community that asks the hard questions and wants to listen to all the answers given in response, even the ones that might sit uncomfortably or require change.

As of late, we have been discussing what it means to be Mennonite andof Anabaptist heritage in today’s world. At one time, Anabaptists were a group that were being persecuted for their faith and ideals, and they felt the need to retreat and seclude themselves in safety away from mainstream culture. But, from what I’ve learned, since WWII, many Mennonites have realized that they have a great deal to offer the world, especially in living out the non-violence teachings of Jesus.

In our Sunday classes, we have had vigorous conversations on the requirements for real, long-lasting peace, as well as the myth of redemptive violence. At one point, someone suggested that instead of fighting back against violence only in overt, active, aggressive ways, we as followers of Jesus need to absorb violence from the worldto keep it from being perpetuated.

So, my mind making the weird connections it does, I immediately thought of : Apollo 13 – you know, that amazing movie with Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton (RIP), and Lieutenant Dan. There is one period in the movie where a crisis evolved over the high levels of carbon dioxide building up in the module the astronauts were in, the result of them exhaling gaseous wastes from their bodies without a working air filtration system. The scientists on the ground in Houston saw that the required oxygen levels were fine, but CO2 was gradually increasing and would reach toxic levels if not dealt with quickly. NASA engineers frantically went to work, using materials available to the flight crew, to create scrubbers that would draw the excess CO2 out of the air and safely contain it.

I picture in my mind non-violent followers of Jesus or Buddha or name-your-guru who act as violence scrubbers in the world. People who can handle bad, hard things and pull away the violent spirit of those things from humanity. But what does that look like? And how to people who scrub the world free of violence not be hardened and broken from the horrors and injustice that occur everyday?

Richard Rohr, that great Franciscan contemplative who I love to quote, frequently remarks that if we don’t transform our pain, we will transmit it. And the problem is, most people have no clue how to transform their pain. We do everything possible to distract ourselves from it, cover it up, blame it on everything outside of ourselves – but we continue to suffer and remain imprisoned and burdened by suffering.

This is what Rohr says true spirituality is about: learning what to do with our pain and suffering. And when we learn how to deal with our own personal suffering, we carve out space to be able to hold the suffering of others. Not in a neurotic, codependent way, but in such a way that transforms it, changes it fundamentally. My mind is now going to the idea of catalytic converters….I will refrain from jumping onto that metaphor here.

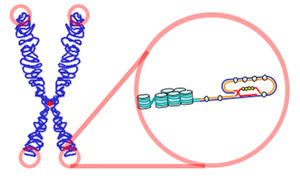

One of my favorite Buddhist teachers, Pema Chodron, teaches a practicethat reminds me of violence scrubbing and pain transformation. It is called Tonglen meditation, and if I understand correctly, is part of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions. According to Pema, we each have a soft spot inside of us, where we are vulnerable and have the capacity for compassion towards ourselves and others. We often close this space up because of fear and involuntarily harden ourselves against our pain and the pain of others. Tonglen is a breathing practice that is about learning to be willing to take in the pain and suffering of others, and then sending back happiness to everyone. She writes that if we can learn to tolerate and sit with pain and hard things within ourselves, we learn not to fear them, and “we increase our capacity for fear and equanimity.”

“We breathe in what is painful and unwanted with the sincere wish that we and others could be free of suffering. As we do so, we drop the story line that goes along with the pain and feel the underlying energy. We completely open our hearts and minds to whatever arises. Exhaling, we sent out relief from the pain with the intention that we and others be happy.” ((The Places That Scare You: A Guide to Fearlessness in Difficult Times).

Every so often a great person rises that embodies violence scrubbing. Mother Teresa, Ghandi, Martin Luther King, Jr., the Dalai Lama, Desmund Tutu…just to name a few of the more well-known ones. Somehow, they have taken on the corporate pain of thousands of people without having it break them, and we have all benefited as a result.

It seems like the last year has seen ever-rising levels of toxicity in our world, with countless varieties of violence threatening the achievement of a lasting peace. At the same time, so many people are turning their backs on religion, with good reason, especially when religious institutions align themselves with the propagation and endorsement of violence. But we can’t rely on a few greats like those I mentioned above to save us. We must find in ourselves the courage to face our pain so that we don’t keep passing it on to our children. Like the astronauts of Apollo 13, we don’t have the choice to sit back and hope we’ll arrive at our destination before we breach a toxicity threshold. We need to grasp on to mature spirituality, use the tools we have at our disposal, and “be the change we want to see in the world.” (Ghandi)